As we move forward in 2023, with a new Congress convened, concerns about the debt ceiling have taken center stage.

What is the debt ceiling?

The debt ceiling is the legal limit on the total amount the U.S. federal government can borrow to finance federal spending. The current debt limit is $31.385 trillion—about 120% of GDP, the highest it’s been since World War II.

The crux of the issue facing the nation is that Congress has passed two contradictory laws. The debt ceiling limits federal borrowing (and, arguably, conflicts with the 14th Amendment’s debt clause, which proclaims that “U.S. debt shall not be questioned”). At the same time, Congress approves federal spending. When Congress knowingly approves spending bills that exceed tax revenues (or approves tax cuts that reduce tax revenues below preapproved spending levels), simple arithmetic tells us that the government will need to borrow to finance the difference. That difference—the deficit—is the shortfall between tax revenues and government spending in any given fiscal year (which runs from October 1 to September 30). The federal debt outstanding is the sum total of annual deficits incurred in prior fiscal years.

If this sounds nonsensical, that’s because it is. This political charade—passing two contradictory laws, one that potentially violates the 14th Amendment—is analogous to purchasing a home and deciding later whether to pay the mortgage. Despite political sound bites suggesting that the federal government should run its finances in ways similar to how American families run their households, I don’t know of many Americans who run up their credit card bills or take out mortgages only to decide later whether to make their payments. In my view, the debt ceiling serves no legitimate fiscal purpose (if its purpose was to cap federal spending, it has clearly failed) and is nothing more than politics. It does nothing except inject uncertainty into financial markets. Unfortunately, in the end, it results in higher borrowing costs for taxpayers and consumers.

The federal budget and the economy

None of this should suggest that federal spending should continue with business as usual. It shouldn’t. We’ve known for decades that federal spending is out of control, that the U.S. faces serious demographic challenges (especially an aging workforce), and that spending reform is needed. Both political parties have failed to appropriately address these issues, and both are equally to blame for the stratospheric rise in federal debt through an irresponsible combination of unfunded tax cuts and unfunded spending. However, severe cuts to federal spending—which comprises about 21% of GDP—would further impair an economy already facing severe economic headwinds and would add to already-growing recessionary pressures. Alternatively, continuing to run trillion-dollar deficits year after year is simply unsustainable at a time when both U.S. population growth and labor productivity have moderated significantly from their past levels. If there was ever a time for our political leadership to cast aside partisanship and compromise, it is now.

Paying down our debt is hard

Some argue that the U.S. government should begin paying down its debt. This sounds great in theory. Whether it’s a practical policy is unknown. There is, after all, significant demand for U.S. Treasury bonds by investors of all types, and reducing the supply of those bonds would force retirees and pensions to invest in relatively risky assets. But that discussion is a bit academic, given the unlikelihood of meaningful debt reduction any time soon.

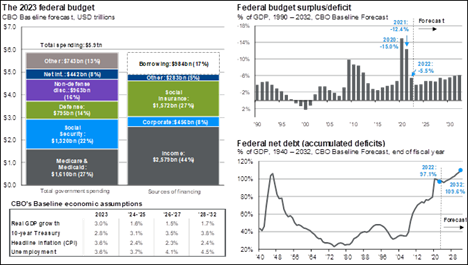

But why does paying down our debt seem so unlikely? Because it would first require balancing the budget, an exercise that continues to prove extremely difficult. Approximately 50% of all federal spending is on cherished social programs like Social Security and Medicare; that share rises to 63% when we include defense spending (also highly cherished) and increases further still, to 71%, when we include the interest on our debt (which will rise dramatically this year, given the significant increase in interest rates). To balance the budget without cutting these cherished programs—and without defaulting on our debt—would likely require eliminating all nondefense discretionary spending (and more), which includes funding for everything from roads, bridges, and ports to schools, scientific research, and environmental protection. If balancing the budget were easy, we’d have done it already. This is the hard work we’ve sent our elected officials to Washington to do.

Exhibit A: the federal budget1

1 Guide to the Markets, J.P. Morgan Asset Management, January 23, 2023.

Why is the debt ceiling such a big deal?

The value of nearly every economy and every financial asset on Earth is ultimately, in some way, supported by the credit rating of the U.S. government. It’s not a stretch to say, more broadly, that the United States continues to underpin the global economic and political order that’s endured since the end of World War II. Playing chicken with the credit rating of the world’s most powerful and important sovereign currency—the U.S. dollar—poses serious economic, financial, and geopolitical risks.

If the debt ceiling isn’t increased (or, better yet, abolished altogether), the federal government will be unable to pay its bills. It’s simple arithmetic. Social Security, Medicare, veterans’ benefits, and—of special concern to financial markets—interest payments on the $31 trillion in debt outstanding—could all be compromised should the federal government run out of money. A default on any one of these, but especially on debt payments, would likely lead to a violent reaction in global financial markets and usher in a severe economic recession.

It’s this last point—specifically, the prospect of a debt default—that concerns most investors. What should we expect in the event that the U.S. government defaults on its debt? Beyond “nothing good,” it’s hard to say for sure. We can look to three recent events to provide some perspective on how markets might react.

1. Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008

During the depths of the 2008 financial crisis, the U.S. House of Representatives initially rejected the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, a package of legislation designed and promoted by then–Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and then–Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke. The goal of that legislation was to prop up the banking system by providing equity capital to banks and much-needed liquidity to help unclog the arteries of the U.S. financial system. When news broke that Congress had rejected the package, the S&P 500 cratered 8.8% and Treasury yields spiked 25 basis points—all in a single day.

2. Debt Downgrade in 2011

Then, as now, Congress was embroiled in a debate over whether to increase the debt ceiling. In response to a seemingly intractable political impasse in Congress, S&P announced a negative outlook for the government’s AAA rating the previous April. Markets initially took the negative outlook in stride, but when S&P subsequently lowered the government’s debt rating (to AA+), on August 2, 2011—four days after Congress voted to increase the debt limit—markets reacted violently to the downgrade. The S&P 500 index fell 13% between August 2 and August 8; markets took nearly six months to recover from those losses.

3. Financial Crisis in 2022

A more recent analog is the case of British Prime Minister Liz Truss and her now-infamous “mini-budget.” Truss was chosen by Conservative Party MPs, on July 20, 2022, to assume leadership of the party (and, ultimately, of the country, as prime minister). Truss campaigned on deep tax cuts and a range of other conservative economic policies. But while such ideology may have had broad populist appeal, financial markets responded as if the policies were fiscally irresponsible. Throughout August and early September, financial markets reflected increasing concern that Truss’s fiscal approach would wreak havoc on the British economy.

Between late July and September—a span of only two months—the British pound collapsed 7.3% in value against the U.S. dollar (an astronomical gap for what is typically a very closely tied currency pair). Interest rates on 30-year U.K. bonds doubled (peaking at 5%), and U.K. stocks fell more than 14%. The upheaval nearly forced the entire U.K. pension system into bankruptcy, jeopardizing the retirement security of millions of British pensioners. The backlash was swift and fierce. Prime Minister Truss was forced to resign, on October 20, bookending the shortest term of any prime minister in British history.

However, things didn’t simply return to normal after Truss’s disastrous tenure. While interest rates on 30-year U.K. bonds fell slightly on the news of her resignation, they finished the year at 4%—a full 1.5% above where they stood just prior to her short stint as prime minister. While Truss’s polices have been rescinded, they unfortunately continue to extract a heavy toll on the U.K. economy and its citizens, in the form of significantly higher borrowing costs.

Exhibit B: Interest rates on 30-year British bonds (“gilts”)2

2Bloomberg.

As shown in the chart above, gilts increased significantly in response to Prime Minister Truss’s proposed fiscal policies and remain elevated despite her resignation on October 20, 2022.

The takeaway: markets teach painful lessons in fiscal responsibility

My intent here isn’t to be dramatic but to provide some real-world examples of what happened when politicians pursued actions that most economists, investors, and, by extension, financial markets believed to be fiscally irresponsible. At the same time, it’s important to highlight that in neither situation—the U.S. in 2011 or the U.K. in 2022—did the government actually default on its debt obligations. Policy-makers in each case eventually came to their senses and did the right things.

The key takeaway for investors and policy-makers is that any message indicating that governments are either unwilling or unable to pay their debts—as evidenced by reckless fiscal policy or political impasse—increases risk for investors. And investors will consequently demand a risk premium, in the form of higher interest rates, to assume those risks. It is we citizens, consumers, and taxpayers who bear both the financial burden (higher borrowing costs, higher taxes) and the economic burden (recession, high unemployment) of those higher rates.

Advice for investors

- A financial plan: Not having a plan is planning to fail. A financial plan is our compass during times of turmoil. No hiker in their right mind would embark on a long journey through the wilderness without a map and timeline. Neither should we. And a financial plan shouldn’t be a “set it and forget it” exercise—quite the opposite. The best financial plans are frequently revisited and (often) updated in response to changing life circumstances and new information.

- Work with a trusted partner: Life is complex. So are our balance sheets, how we feel about risk, how we process new information, and how we make decisions. While our feelings about risk, markets, and our financial lives all naturally change over time (and with new information), partnering with a trusted advisor to connect and re-connect the dots can help ensure we make the best-informed decisions possible in times of turmoil.

- Portfolio diversification: Portfolio diversification is about risk management; and risk management is about taking only those risks that make good financial sense. Market timing, panicked selling, or taking concentrated bets on a handful of individual companies or asset classes can introduce unnecessary risk in your portfolio and potentially jeopardize your financial security. When it comes to diversification, more is better—within and across asset classes, both public and private.

- Liquidity: During times of stress, the most important aspect of our balance sheet to consider is its liquidity. Maintaining appropriate cash reserves, lines of credit, and other near-cash equivalents (e.g., money market funds, short-term Treasury bonds) is essential to maintaining one’s sanity and weathering the storm. Your advisor can help assess your family’s liquidity needs and identify appropriate vehicles and near-cash asset classes to help you meet spending demands as they arise.

Home » Insights » Market Commentary » What’s Going on with the Debt Ceiling?

What’s Going on with the Debt Ceiling?

Donald Calcagni, MBA, MST, CFP®, AIF®

Chief Investment Officer

With news focused on the U.S. debt ceiling, many wonder about impacts to portfolios and financial planning. Read on to learn more.

As we move forward in 2023, with a new Congress convened, concerns about the debt ceiling have taken center stage.

What is the debt ceiling?

The debt ceiling is the legal limit on the total amount the U.S. federal government can borrow to finance federal spending. The current debt limit is $31.385 trillion—about 120% of GDP, the highest it’s been since World War II.

The crux of the issue facing the nation is that Congress has passed two contradictory laws. The debt ceiling limits federal borrowing (and, arguably, conflicts with the 14th Amendment’s debt clause, which proclaims that “U.S. debt shall not be questioned”). At the same time, Congress approves federal spending. When Congress knowingly approves spending bills that exceed tax revenues (or approves tax cuts that reduce tax revenues below preapproved spending levels), simple arithmetic tells us that the government will need to borrow to finance the difference. That difference—the deficit—is the shortfall between tax revenues and government spending in any given fiscal year (which runs from October 1 to September 30). The federal debt outstanding is the sum total of annual deficits incurred in prior fiscal years.

If this sounds nonsensical, that’s because it is. This political charade—passing two contradictory laws, one that potentially violates the 14th Amendment—is analogous to purchasing a home and deciding later whether to pay the mortgage. Despite political sound bites suggesting that the federal government should run its finances in ways similar to how American families run their households, I don’t know of many Americans who run up their credit card bills or take out mortgages only to decide later whether to make their payments. In my view, the debt ceiling serves no legitimate fiscal purpose (if its purpose was to cap federal spending, it has clearly failed) and is nothing more than politics. It does nothing except inject uncertainty into financial markets. Unfortunately, in the end, it results in higher borrowing costs for taxpayers and consumers.

The federal budget and the economy

None of this should suggest that federal spending should continue with business as usual. It shouldn’t. We’ve known for decades that federal spending is out of control, that the U.S. faces serious demographic challenges (especially an aging workforce), and that spending reform is needed. Both political parties have failed to appropriately address these issues, and both are equally to blame for the stratospheric rise in federal debt through an irresponsible combination of unfunded tax cuts and unfunded spending. However, severe cuts to federal spending—which comprises about 21% of GDP—would further impair an economy already facing severe economic headwinds and would add to already-growing recessionary pressures. Alternatively, continuing to run trillion-dollar deficits year after year is simply unsustainable at a time when both U.S. population growth and labor productivity have moderated significantly from their past levels. If there was ever a time for our political leadership to cast aside partisanship and compromise, it is now.

Paying down our debt is hard

Some argue that the U.S. government should begin paying down its debt. This sounds great in theory. Whether it’s a practical policy is unknown. There is, after all, significant demand for U.S. Treasury bonds by investors of all types, and reducing the supply of those bonds would force retirees and pensions to invest in relatively risky assets. But that discussion is a bit academic, given the unlikelihood of meaningful debt reduction any time soon.

But why does paying down our debt seem so unlikely? Because it would first require balancing the budget, an exercise that continues to prove extremely difficult. Approximately 50% of all federal spending is on cherished social programs like Social Security and Medicare; that share rises to 63% when we include defense spending (also highly cherished) and increases further still, to 71%, when we include the interest on our debt (which will rise dramatically this year, given the significant increase in interest rates). To balance the budget without cutting these cherished programs—and without defaulting on our debt—would likely require eliminating all nondefense discretionary spending (and more), which includes funding for everything from roads, bridges, and ports to schools, scientific research, and environmental protection. If balancing the budget were easy, we’d have done it already. This is the hard work we’ve sent our elected officials to Washington to do.

Exhibit A: the federal budget1

1 Guide to the Markets, J.P. Morgan Asset Management, January 23, 2023.

Why is the debt ceiling such a big deal?

The value of nearly every economy and every financial asset on Earth is ultimately, in some way, supported by the credit rating of the U.S. government. It’s not a stretch to say, more broadly, that the United States continues to underpin the global economic and political order that’s endured since the end of World War II. Playing chicken with the credit rating of the world’s most powerful and important sovereign currency—the U.S. dollar—poses serious economic, financial, and geopolitical risks.

If the debt ceiling isn’t increased (or, better yet, abolished altogether), the federal government will be unable to pay its bills. It’s simple arithmetic. Social Security, Medicare, veterans’ benefits, and—of special concern to financial markets—interest payments on the $31 trillion in debt outstanding—could all be compromised should the federal government run out of money. A default on any one of these, but especially on debt payments, would likely lead to a violent reaction in global financial markets and usher in a severe economic recession.

It’s this last point—specifically, the prospect of a debt default—that concerns most investors. What should we expect in the event that the U.S. government defaults on its debt? Beyond “nothing good,” it’s hard to say for sure. We can look to three recent events to provide some perspective on how markets might react.

1. Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008

During the depths of the 2008 financial crisis, the U.S. House of Representatives initially rejected the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, a package of legislation designed and promoted by then–Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson and then–Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke. The goal of that legislation was to prop up the banking system by providing equity capital to banks and much-needed liquidity to help unclog the arteries of the U.S. financial system. When news broke that Congress had rejected the package, the S&P 500 cratered 8.8% and Treasury yields spiked 25 basis points—all in a single day.

2. Debt Downgrade in 2011

Then, as now, Congress was embroiled in a debate over whether to increase the debt ceiling. In response to a seemingly intractable political impasse in Congress, S&P announced a negative outlook for the government’s AAA rating the previous April. Markets initially took the negative outlook in stride, but when S&P subsequently lowered the government’s debt rating (to AA+), on August 2, 2011—four days after Congress voted to increase the debt limit—markets reacted violently to the downgrade. The S&P 500 index fell 13% between August 2 and August 8; markets took nearly six months to recover from those losses.

3. Financial Crisis in 2022

A more recent analog is the case of British Prime Minister Liz Truss and her now-infamous “mini-budget.” Truss was chosen by Conservative Party MPs, on July 20, 2022, to assume leadership of the party (and, ultimately, of the country, as prime minister). Truss campaigned on deep tax cuts and a range of other conservative economic policies. But while such ideology may have had broad populist appeal, financial markets responded as if the policies were fiscally irresponsible. Throughout August and early September, financial markets reflected increasing concern that Truss’s fiscal approach would wreak havoc on the British economy.

Between late July and September—a span of only two months—the British pound collapsed 7.3% in value against the U.S. dollar (an astronomical gap for what is typically a very closely tied currency pair). Interest rates on 30-year U.K. bonds doubled (peaking at 5%), and U.K. stocks fell more than 14%. The upheaval nearly forced the entire U.K. pension system into bankruptcy, jeopardizing the retirement security of millions of British pensioners. The backlash was swift and fierce. Prime Minister Truss was forced to resign, on October 20, bookending the shortest term of any prime minister in British history.

However, things didn’t simply return to normal after Truss’s disastrous tenure. While interest rates on 30-year U.K. bonds fell slightly on the news of her resignation, they finished the year at 4%—a full 1.5% above where they stood just prior to her short stint as prime minister. While Truss’s polices have been rescinded, they unfortunately continue to extract a heavy toll on the U.K. economy and its citizens, in the form of significantly higher borrowing costs.

Exhibit B: Interest rates on 30-year British bonds (“gilts”)2

2Bloomberg.

As shown in the chart above, gilts increased significantly in response to Prime Minister Truss’s proposed fiscal policies and remain elevated despite her resignation on October 20, 2022.

The takeaway: markets teach painful lessons in fiscal responsibility

My intent here isn’t to be dramatic but to provide some real-world examples of what happened when politicians pursued actions that most economists, investors, and, by extension, financial markets believed to be fiscally irresponsible. At the same time, it’s important to highlight that in neither situation—the U.S. in 2011 or the U.K. in 2022—did the government actually default on its debt obligations. Policy-makers in each case eventually came to their senses and did the right things.

The key takeaway for investors and policy-makers is that any message indicating that governments are either unwilling or unable to pay their debts—as evidenced by reckless fiscal policy or political impasse—increases risk for investors. And investors will consequently demand a risk premium, in the form of higher interest rates, to assume those risks. It is we citizens, consumers, and taxpayers who bear both the financial burden (higher borrowing costs, higher taxes) and the economic burden (recession, high unemployment) of those higher rates.

Advice for investors

Explore More

Diversification: What It Is and What It Isn’t

Implications of The Market Response To the Election: Insights From Our CIO

Energy Prices on the Eve of the Election: Insights From Our CIO

Mercer Advisors Inc. is the parent company of Mercer Global Advisors Inc. and is not involved with investment services. Mercer Global Advisors Inc. (“Mercer Advisors”) is registered as an investment advisor with the SEC. The firm only transacts business in states where it is properly registered or is excluded or exempted from registration requirements.

All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the author as of the date of publication and are subject to change. Some of the research and ratings shown in this presentation come from third parties that are not affiliated with Mercer Advisors. The information is believed to be accurate but is not guaranteed or warranted by Mercer Advisors. Content, research, tools and stock or option symbols are for educational and illustrative purposes only and do not imply a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell a particular security or to engage in any particular investment strategy. For financial planning advice specific to your circumstances, talk to a qualified professional at Mercer Advisors.

Past performance may not be indicative of future results. Therefore, no current or prospective client should assume that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy or product made reference to directly or indirectly, will be profitable or equal to past performance levels. All investment strategies have the potential for profit or loss. Changes in investment strategies, contributions or withdrawals may materially alter the performance and results of your portfolio. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that any specific investment will either be suitable or profitable for a client’s investment portfolio. Diversification does not ensure a profit or guarantee against a loss. Historical performance results for investment indexes and/or categories, generally do not reflect the deduction of transaction and/or custodial charges or the deduction of an investment-management fee, the incurrence of which would have the effect of decreasing historical performance results. Economic factors, market conditions, and investment strategies will affect the performance of any portfolio and there are no assurances that it will match or outperform any particular benchmark.