This past weekend President Trump levied tariffs against imports from Canada, Mexico, and China. All three countries have announced retaliatory tariffs in response. Mexico, at least, quickly negotiated a reprieve. Global financial markets initially reacted with volatility. The below is an attempt to provide a non-political assessment of the economic impact of tariffs and their subsequent investment implications.

What is a tariff?

Tariffs are a type of tax that is assessed on the value of imported goods from other countries. The tariff is charged to the importer of that good. It is President Trump’s view that tariff revenue collected by the U.S. federal government can be used to fund tax cuts and bring down the U.S. federal deficit.

The importer of tariffed goods can push the cost of tariffs on to both consumers (buyers) and non-U.S. producers (sellers). At one end of the spectrum, most or all of the cost may fall on consumers (the American people). This is most common. Alternatively, at the other end of the spectrum, foreign producers may be forced to absorb most or all of the cost themselves, pushing down profits and (likely) the enterprise value of the business (i.e., stock prices). For obvious reasons, this is relatively rare. In practice, both buyers and sellers are typically harmed, to varying degrees, by the imposition of tariffs.

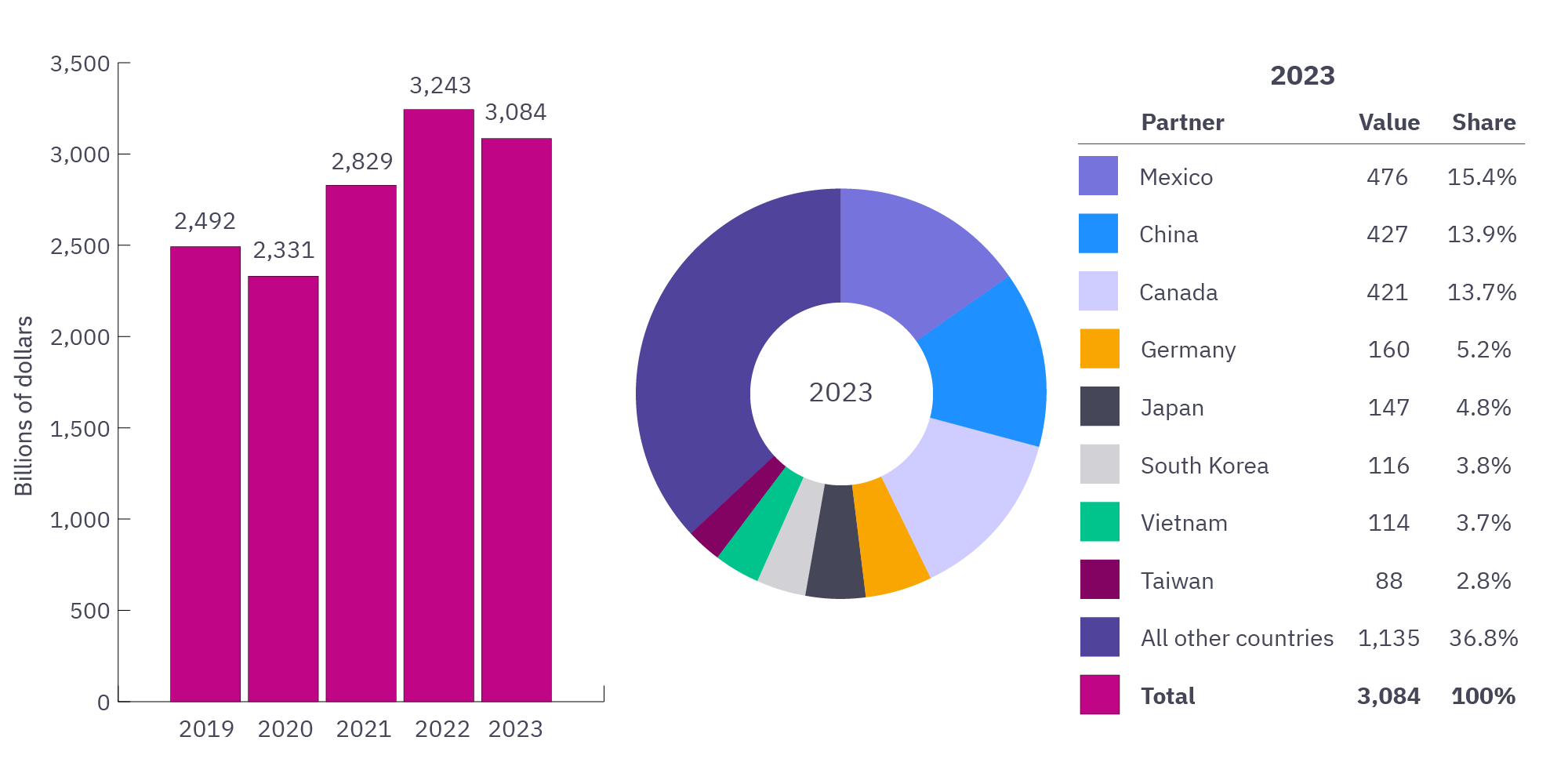

Figure 1: U.S. general imports, by selected trading partners, 2019-23.

Source: United States International Trade Commission.

Are tariffs inflationary?

In most real-world cases, tariffs lead to additional costs for consumers. Consequently, tariffs often contribute to higher inflation.

Tariffs have a direct and immediate impact on consumer prices. In this regard, they’re not unlike other taxes. Sales taxes on cigarettes, gasoline, alcohol, firearms, and many other goods all push their respective prices higher than consumer demand alone would justify. Indeed, the purpose of such policies is to raise their prices to make them relatively less desirable.

However, tariffs also push prices higher in less obvious ways. For example, higher costs (resulting in lower profit margins) force businesses to produce and sell less or to withdraw or shrink their footprints in certain markets (e.g., the U.S.). This naturally increases the relative scarcity of those goods that consumers would otherwise like to purchase. Additionally, the imposition of tariffs to protect U.S. companies provides them with a degree of monopoly power (i.e., pricing power) that they otherwise wouldn’t enjoy, allowing them to charge higher prices for their goods produced domestically.

Are there perhaps exceptions, or situations, where tariffs would not raise consumer prices?

Yes, but only in theory. If consumer demand for a particular product is perfectly elastic — meaning that any increase in price would result in an immediate and corresponding drop in demand — then a rise in the price of the good in question would not be inflationary because consumers would no longer purchase it. This is because consumers would — again in theory — simply decide to purchase substitute products that are freely available in the market pre-tariff prices. However, should this be the case, we should note that the federal government would therefore collect no tariff revenue since the tariffed products would have no buyers. There would consequently be no need for tariffs in the first place.

However, we should note this is a theoretical case that we just don’t see often in the real world. Just this morning, a study by J.P. Morgan argues that the tariffs announced this weekend against Mexico, Canada, and China would lead to an increase in inflation of just over 1%; said differently, J.P. Morgan estimates that these tariffs alone would cost U.S. households a staggering $300 billion annually.1

What does President Trump hope to achieve with tariffs?

President Trump has argued that tariffs should be used to entice U.S. manufacturing companies to locate (or relocate) production to the United States; to raise revenue to bring down the U.S. federal deficit; and to reduce or eliminate trade imbalances between the U.S. and other countries. The relative merits of these claims have been evaluated and debated for years within academic and industry circles among economists.

Won’t tariffs bring back manufacturing to the U.S.?

This is highly unlikely. Economists generally agree that the decline in U.S. manufacturing over the past 30 years is largely due to advances in automation, not outsourcing or trade policy. Further, this argument assumes a simple world of two (or relatively few countries). Just because the U.S. levies tariffs on China doesn’t mean manufacturing jobs should move to the U.S. Companies have many choices where to locate production.

For example, Mexico has been the largest beneficiary of the tariffs imposed by the first Trump administration against China in 2018. Further, relocating manufacturing facilities and readjusting supply chains is a long, expensive, and arduous proposition for most companies. Finally, tariffs don’t change the fact that, for a host of reasons, the cost of production in the U.S. is much higher than in the rest of the world (e.g., higher labor costs, stricter environmental standards, etc.). Tariffs don’t change this economic reality.

What are the likely economic and investment implications of tariffs?

The most immediate impact of U.S.-levied tariffs is higher prices for U.S. households. And with consumer spending making up approximately 70% of all U.S. economic activity, the impact on the economy can be swift and substantial. The Tax Foundation an organization providing independent analysis and data-driven insights, estimates the impact, estimates the impact of President Trump’s newly announced tariffs would be a staggering $1.1 trillion in higher taxes between 2025 and 2034, shaving 0.4% off annual GDP growth.2

There are other potential impacts, some of which could be significant. For example, retaliatory tariffs from other countries could affect key U.S. industries like energy, agricultural goods, electronics, and lumber — some of our largest exports. This might lead to changes in employment within certain regions and sectors. Additionally, tariffs could result in adjustments to prices and sales for investors, potentially affecting corporate profits and stock prices. Higher consumer prices may also lead the U.S. Federal Reserve to consider changes in interest rates, impacting stocks and other assets.

Some argue that the imposition of tariffs would result in job gains, as newly protected industries would expand to meet consumer demand. However, the evidence doesn’t support this conclusion. Consider the case of Whirlpool. Six months after President Trump announced new tariffs in 2018 (at the request of Whirlpool and other U.S. manufacturers), its stock price was down 15% and net income was down $64 million for the quarter from a year earlier. In fact, economists estimate that President Trump’s 2018 tariffs (which former President Biden largely left in place) resulted in a loss of $3.4 billion in downstream production between 2018 and 2021.3

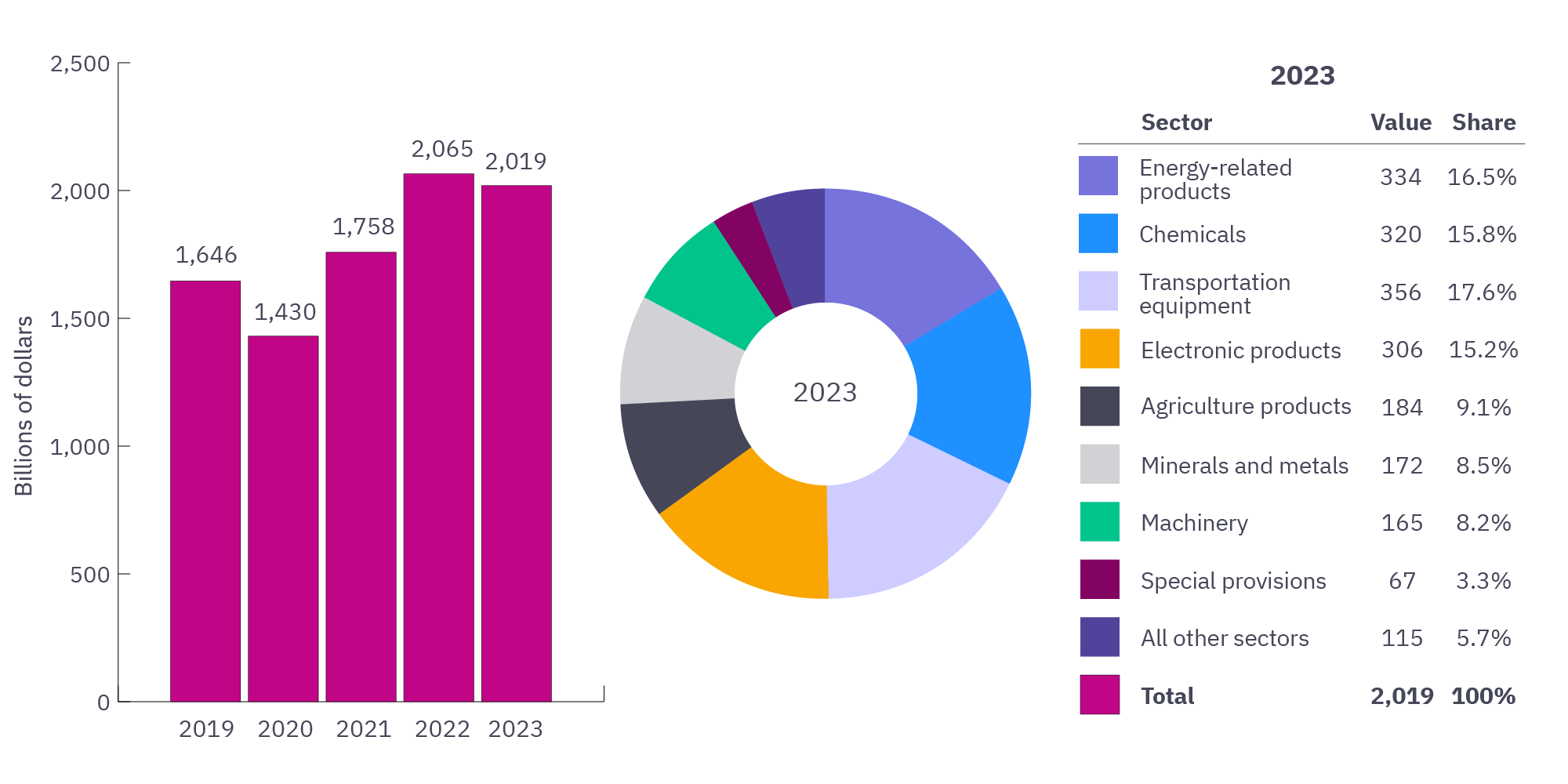

Figure 2: U.S. total exports by major industry/commodity sectors, trading partners, 2019 – 23.

Source: United States International Trade Commission.

Key takeaways

While the tariffs aim to protect certain industries, in the short term, they will likely contribute to inflation. None of this is to suggest that tariffs are the only factor that influence consumer prices. Federal Reserve policy, fiscal policy, exchange rates, and many other factors all work in complex ways to impact inflation and the broader economy. But there should be no mistake that tariffs will likely have a negative impact the cost of everyday items including groceries, electronics, and other goods.

The policy environment remains very uncertain. President Trump often uses tariffs as a negotiation tactic, and he may impose or pause them at any time.

For instance, during the writing of this article, he decided to pause the imposition of U.S. tariffs against Mexico, leading to a recovery in U.S. equity markets from their early morning losses. This policy uncertainty is a powerful headwind for the U.S. economy and financial markets.

Stay diversified. With the policy environment changing quickly, investors would be wise to resist the urge to make investment changes in their portfolios based on any perceived, announced, or implemented policies coming out of the White House. Amid such uncertainty, the wisest approach remains to keep our portfolios as broadly diversified as possible and to avoid unnecessary concentration in specific companies, sectors, asset classes, or countries. Investors would be wise to work double time with their advisors to hedge and/or diversify growth stocks, especially technology stocks trading at nosebleed valuations. A healthy mix of global stocks, bonds, cash, and real assets — across both public and private markets — remains the most prudent path forward.

Click here for past insights from our CIO about the impact of the election on markets and other interesting topics. Not a Mercer Advisors client but interested in more information? Let’s talk.

1 Notes on the Week Ahead, Episode 290: “The Investment Implication of Trade War” by David Kelly, JP Morgan Asset Management, February 3, 2025.

2 “Trump Tariffs: Tracking the Economic Impact of the Trump Trade War,” Tax Foundation, February 3, 2025

3 “Whirlpool Wanted Washer Tariffs. It Wasn’t Ready for a Trade Showdown,” The Wall Street Journal, July 16, 2018.

Home » Insights » Tariffs, Trade, and Markets: Insights From Our CIO

Tariffs, Trade, and Markets: Insights From Our CIO

Donald Calcagni, MBA, MST, CFP®, AIF®

Chief Investment Officer

Tariffs, Trade and Markets. We offer practical considerations on the economic and market impact of tariff policies.

This past weekend President Trump levied tariffs against imports from Canada, Mexico, and China. All three countries have announced retaliatory tariffs in response. Mexico, at least, quickly negotiated a reprieve. Global financial markets initially reacted with volatility. The below is an attempt to provide a non-political assessment of the economic impact of tariffs and their subsequent investment implications.

What is a tariff?

Tariffs are a type of tax that is assessed on the value of imported goods from other countries. The tariff is charged to the importer of that good. It is President Trump’s view that tariff revenue collected by the U.S. federal government can be used to fund tax cuts and bring down the U.S. federal deficit.

The importer of tariffed goods can push the cost of tariffs on to both consumers (buyers) and non-U.S. producers (sellers). At one end of the spectrum, most or all of the cost may fall on consumers (the American people). This is most common. Alternatively, at the other end of the spectrum, foreign producers may be forced to absorb most or all of the cost themselves, pushing down profits and (likely) the enterprise value of the business (i.e., stock prices). For obvious reasons, this is relatively rare. In practice, both buyers and sellers are typically harmed, to varying degrees, by the imposition of tariffs.

Figure 1: U.S. general imports, by selected trading partners, 2019-23.

Source: United States International Trade Commission.

Are tariffs inflationary?

In most real-world cases, tariffs lead to additional costs for consumers. Consequently, tariffs often contribute to higher inflation.

Tariffs have a direct and immediate impact on consumer prices. In this regard, they’re not unlike other taxes. Sales taxes on cigarettes, gasoline, alcohol, firearms, and many other goods all push their respective prices higher than consumer demand alone would justify. Indeed, the purpose of such policies is to raise their prices to make them relatively less desirable.

However, tariffs also push prices higher in less obvious ways. For example, higher costs (resulting in lower profit margins) force businesses to produce and sell less or to withdraw or shrink their footprints in certain markets (e.g., the U.S.). This naturally increases the relative scarcity of those goods that consumers would otherwise like to purchase. Additionally, the imposition of tariffs to protect U.S. companies provides them with a degree of monopoly power (i.e., pricing power) that they otherwise wouldn’t enjoy, allowing them to charge higher prices for their goods produced domestically.

Are there perhaps exceptions, or situations, where tariffs would not raise consumer prices?

Yes, but only in theory. If consumer demand for a particular product is perfectly elastic — meaning that any increase in price would result in an immediate and corresponding drop in demand — then a rise in the price of the good in question would not be inflationary because consumers would no longer purchase it. This is because consumers would — again in theory — simply decide to purchase substitute products that are freely available in the market pre-tariff prices. However, should this be the case, we should note that the federal government would therefore collect no tariff revenue since the tariffed products would have no buyers. There would consequently be no need for tariffs in the first place.

However, we should note this is a theoretical case that we just don’t see often in the real world. Just this morning, a study by J.P. Morgan argues that the tariffs announced this weekend against Mexico, Canada, and China would lead to an increase in inflation of just over 1%; said differently, J.P. Morgan estimates that these tariffs alone would cost U.S. households a staggering $300 billion annually.1

What does President Trump hope to achieve with tariffs?

President Trump has argued that tariffs should be used to entice U.S. manufacturing companies to locate (or relocate) production to the United States; to raise revenue to bring down the U.S. federal deficit; and to reduce or eliminate trade imbalances between the U.S. and other countries. The relative merits of these claims have been evaluated and debated for years within academic and industry circles among economists.

Won’t tariffs bring back manufacturing to the U.S.?

This is highly unlikely. Economists generally agree that the decline in U.S. manufacturing over the past 30 years is largely due to advances in automation, not outsourcing or trade policy. Further, this argument assumes a simple world of two (or relatively few countries). Just because the U.S. levies tariffs on China doesn’t mean manufacturing jobs should move to the U.S. Companies have many choices where to locate production.

For example, Mexico has been the largest beneficiary of the tariffs imposed by the first Trump administration against China in 2018. Further, relocating manufacturing facilities and readjusting supply chains is a long, expensive, and arduous proposition for most companies. Finally, tariffs don’t change the fact that, for a host of reasons, the cost of production in the U.S. is much higher than in the rest of the world (e.g., higher labor costs, stricter environmental standards, etc.). Tariffs don’t change this economic reality.

What are the likely economic and investment implications of tariffs?

The most immediate impact of U.S.-levied tariffs is higher prices for U.S. households. And with consumer spending making up approximately 70% of all U.S. economic activity, the impact on the economy can be swift and substantial. The Tax Foundation an organization providing independent analysis and data-driven insights, estimates the impact, estimates the impact of President Trump’s newly announced tariffs would be a staggering $1.1 trillion in higher taxes between 2025 and 2034, shaving 0.4% off annual GDP growth.2

There are other potential impacts, some of which could be significant. For example, retaliatory tariffs from other countries could affect key U.S. industries like energy, agricultural goods, electronics, and lumber — some of our largest exports. This might lead to changes in employment within certain regions and sectors. Additionally, tariffs could result in adjustments to prices and sales for investors, potentially affecting corporate profits and stock prices. Higher consumer prices may also lead the U.S. Federal Reserve to consider changes in interest rates, impacting stocks and other assets.

Some argue that the imposition of tariffs would result in job gains, as newly protected industries would expand to meet consumer demand. However, the evidence doesn’t support this conclusion. Consider the case of Whirlpool. Six months after President Trump announced new tariffs in 2018 (at the request of Whirlpool and other U.S. manufacturers), its stock price was down 15% and net income was down $64 million for the quarter from a year earlier. In fact, economists estimate that President Trump’s 2018 tariffs (which former President Biden largely left in place) resulted in a loss of $3.4 billion in downstream production between 2018 and 2021.3

Figure 2: U.S. total exports by major industry/commodity sectors, trading partners, 2019 – 23.

Source: United States International Trade Commission.

Key takeaways

While the tariffs aim to protect certain industries, in the short term, they will likely contribute to inflation. None of this is to suggest that tariffs are the only factor that influence consumer prices. Federal Reserve policy, fiscal policy, exchange rates, and many other factors all work in complex ways to impact inflation and the broader economy. But there should be no mistake that tariffs will likely have a negative impact the cost of everyday items including groceries, electronics, and other goods.

The policy environment remains very uncertain. President Trump often uses tariffs as a negotiation tactic, and he may impose or pause them at any time.

For instance, during the writing of this article, he decided to pause the imposition of U.S. tariffs against Mexico, leading to a recovery in U.S. equity markets from their early morning losses. This policy uncertainty is a powerful headwind for the U.S. economy and financial markets.

Stay diversified. With the policy environment changing quickly, investors would be wise to resist the urge to make investment changes in their portfolios based on any perceived, announced, or implemented policies coming out of the White House. Amid such uncertainty, the wisest approach remains to keep our portfolios as broadly diversified as possible and to avoid unnecessary concentration in specific companies, sectors, asset classes, or countries. Investors would be wise to work double time with their advisors to hedge and/or diversify growth stocks, especially technology stocks trading at nosebleed valuations. A healthy mix of global stocks, bonds, cash, and real assets — across both public and private markets — remains the most prudent path forward.

Click here for past insights from our CIO about the impact of the election on markets and other interesting topics. Not a Mercer Advisors client but interested in more information? Let’s talk.

1 Notes on the Week Ahead, Episode 290: “The Investment Implication of Trade War” by David Kelly, JP Morgan Asset Management, February 3, 2025.

2 “Trump Tariffs: Tracking the Economic Impact of the Trump Trade War,” Tax Foundation, February 3, 2025

3 “Whirlpool Wanted Washer Tariffs. It Wasn’t Ready for a Trade Showdown,” The Wall Street Journal, July 16, 2018.

Mercer Advisors Inc. is a parent company of Mercer Global Advisors Inc. and is not involved with investment services. Mercer Global Advisors Inc. (“Mercer Advisors”) is registered as an investment advisor with the SEC. The firm only transacts business in states where it is properly registered or is excluded or exempted from registration requirements.

All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the author as of the date of publication and are subject to change. Some of the research and ratings shown in this presentation come from third parties that are not affiliated with Mercer Advisors. The information is believed to be accurate but is not guaranteed or warranted by Mercer Advisors. Content, research, tools and stock or option symbols are for educational and illustrative purposes only and do not imply a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell a particular security or to engage in any particular investment strategy. For financial planning advice specific to your circumstances, talk to a qualified professional at Mercer Advisors.

Past performance may not be indicative of future results. Therefore, no current or prospective client should assume that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy or product made reference to directly or indirectly, will be profitable or equal to past performance levels. All investment strategies have the potential for profit or loss. Changes in investment strategies, contributions or withdrawals may materially alter the performance and results of your portfolio. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that any specific investment will either be suitable or profitable for a client’s investment portfolio. Diversification does not ensure a profit or guarantee against loss. Historical performance results for investment indexes and/or categories, generally do not reflect the deduction of transaction and/or custodial charges or the deduction of an investment-management fee, the incurrence of which would have the effect of decreasing historical performance results. Economic factors, market conditions, and investment strategies will affect the performance of any portfolio and there are no assurances that it will match or outperform any particular benchmark.

This document may contain forward-looking statements including statements regarding our intent, belief or current expectations with respect to market conditions. Readers are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements. While due care has been used in the preparation of forecast information, actual results may vary in a materially positive or negative manner. Forecasts and hypothetical examples are subject to uncertainty and contingencies outside Mercer Advisors’ control.

Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards, Inc. (CFP Board) owns the CFP® certification mark, the CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ certification mark, and the CFP® certification mark (with plaque design) logo in the United States, which it authorizes use of by individuals who successfully complete CFP Board’s initial and ongoing certification requirements.

Explore More

Why We Talk About “Investment Programs” Instead of “Model Portfolios”

Initial Thoughts on the DeepSeek Selloff: Insights From Our CIO

Is Bitcoin an Investable Asset? Not Yet: Insights From Our CIO