Ready to learn more?

Home » Insights » Estate Planning » 3 Phases of a Lifelong Financial Plan for People With Disabilities

Christopher Currin, CFP®, ChSNC®

Sr. Wealth Strategist

Lifelong planning for folks with disabilities is often a balancing act between providing support and not undermining existing benefits.

Chances are good that you, or someone you know, is taking care of a person with an underlying health condition or impairment. While each circumstance is unique, when thinking of the financial planning process for people with disabilities, breaking it up into three phases can help with optimizing available resources and ensuring that an individual with a disability has vital support over their lifetime. First, prepare for the worst-case scenario. Second, enhance security. Third, create better-case scenarios.

Four cornerstones for support

As part of a financial plan, it’s important to consider the government programs that make up the four cornerstones of support that many people need during their lifetime: 1) Social Security Retirement Benefits, 2) Social Security Disability Insurance, 3) Supplemental Security Income, and 4) Medicare or Medicaid.

Gaining and maintaining eligibility for key government programs can help build a financial foundation for those with health conditions or impairments.

The four cornerstones may not be enough

The four cornerstones, though valuable, are generally not enough. Supplementing these benefits without undermining or endangering eligibility for SSI and Medicaid is a challenge many people will likely face. For example, let’s say an adult with a disability receives SSI and Medicaid and, after a few years, a parent passes away, leaving them a $100,000 life insurance benefit. The inheritance not only disqualifies them from means-tested programs, but also can be confiscated by the state for repayment of benefits previously paid. This is an example of a worst-case scenario: The parents tried to support their child, who happens to be an adult with a disability, but their life insurance money never reached the intended beneficiary and resulted in a loss of government benefits too.

How can you ensure that a person with a health condition or impairment doesn’t lose benefits as the result of a life insurance payout or other asset transfer?

Three phases of a financial plan

1. Preparing for the worst-case scenario

A discretionary trust (also called a supplemental or special needs trust) is meant to ensure that assets can be set aside for a person with a disability without endangering their means-tested benefits.

There are three variations:

Third-party trust: Created, managed, and funded by someone other than the beneficiary. After being set up by the grantor, the third-party trust provides ongoing support to the person with a disability without displacing their public benefits and, when the beneficiary dies, the assets can go to another heir without a clawback of benefits previously paid by the state.

Master pooled trust: Individuals or families with insufficient assets to create a third-party trust could consider a master pooled trust. Typically run by a nonprofit organization, this trust aggregates assets for investment and management purposes, then creates subaccounts for each beneficiary.

First-party trust, or Medicaid payback trust: Funded with assets that are owned by the beneficiary. If, for example, the individual receives a large jury award, it can be added to the trust. By giving up control of the assets, the beneficiary can often maintain means-tested benefits and then take distributions from the trust for additional financial support. Any assets that remain after the beneficiary dies are subject to reclamation by the state.

Be sure to consult a legal or tax professional to determine whether a discretionary trust is right for your situation.

2. Enhancing security

Cornerstone public programs are financial foundations for people with special needs. Estate planning is the plumbing that can deliver cash flow for supplemental needs without undermining the foundation. And a comprehensive financial plan is a framework for the foundation, specifically designed to enable a good life. The next step is to wrap the framework with a layer of protection against other perils that can lead to financial ruin.

Enhancing security also means assessing insurance needs. Unpaid medical bills are a leading cause of bankruptcy. Health insurance often becomes the most critical need after a disability is diagnosed. Also, because a disability typically increases expenses and decreases an individual’s or family’s income, life insurance should be assessed as well.

Your typical financial life cycle includes: a dependency period when you rely on parents for support; an accumulation phase when you are self-supporting and building your savings; and a distribution phase when you leave the workforce and live on pensions and income from your accumulated assets. Because a person with a disability typically has a shorter accumulation period, their long-term retirement savings goals might need to be substantially different than those of a typical client. In essence, a married couple that has a child with a disability might need to plan a retirement for three people instead of two.

What are some of the tools that can be used to help beef up finances and provide a fuller life for someone with a disability?

Efficient savings can make a substantial difference over time. Qualified retirement plans such as an IRA or 401(k) provide important tax advantages for long-term investors. Health Savings Accounts are also tax-advantaged and can be used not only to pay periodic medical expenses, but also to save for the long term.

In addition, passage of the Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) Act of 2014 created tax advantaged savings accounts for individuals with disabilities diagnosed before age 26. The total contribution to an ABLE account in a single tax year is capped at $18,000, and the first $100,000 in an account is exempt from the SSI $2,000 individual resource limit.

For more information on creating a financial plan: Financial Planning for Individuals with Disabilities.

3. Creating better-case scenarios

All this planning, insuring, saving, and investing is meant to help enable people with disabilities to live secure and meaningful lives. That means shifting the focus from what’s important for them to what’s important to them — from their needs to their dreams. Their aspirations are not unlike those of their peers, thanks in part to the inclusion of children with disabilities in our public schools since the mid-1970s. Today the frontiers of inclusion are expanding rapidly in both post-secondary education and employment opportunities. There may be challenges in preventing hard-earned money from interfering with essential public benefits, but ultimately everyone can gain when all of us are allowed to make our unique contribution to a community that supports and values us.

People with disabilities and their allies continue to seek new opportunities to enjoy a good life. Since the passage of the Higher Education Opportunity Act in 2008, more than 300 post-secondary programs for people with intellectual disabilities have been created to provide access to college courses and campus life for a more diverse student body.4 Nearly 4 million athletes compete in Special Olympics in 177 countries.5 Nearly 19 million people with disabilities are in the workforce, but that represents less than 40% of the group’s working age population.6 There is a critical shortage of supportive housing as vast numbers of adults with disabilities still live at home with aging parent caretakers. So much remains to be done to make it possible to create better lives for our friends and loved ones with disabilities.

Create your lifelong financial plan

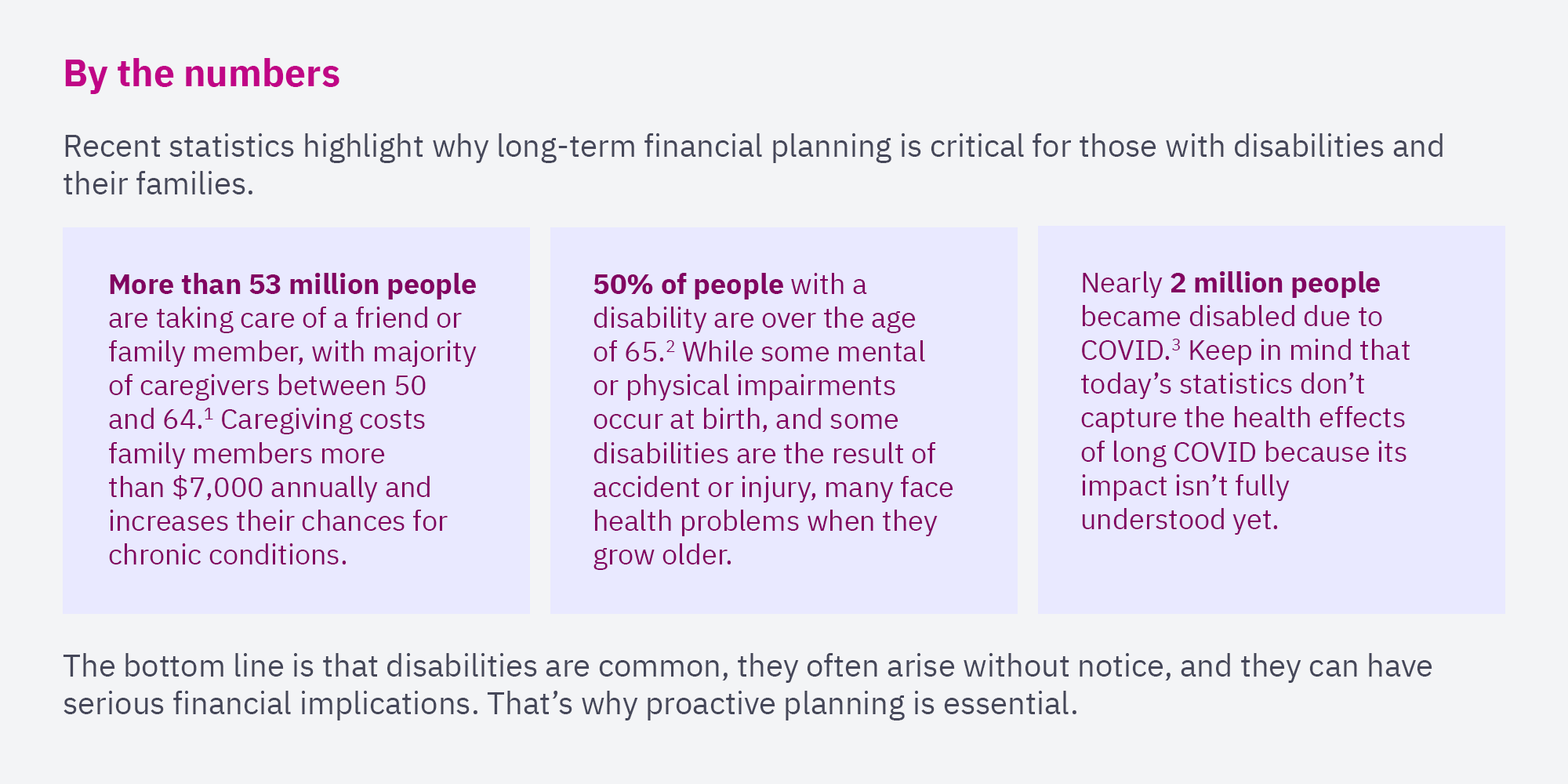

Roughly one in four adult Americans has some type of significant disability.7 Disabilities can happen unexpectedly to anyone, thwarting even the most thorough financial plan. While government programs can offer cornerstones of support, they’re often not enough. Looking at a lifelong financial plan in terms of three phases — preparing for the worst-case scenario, enhancing security, and creating better-case scenarios — can help preserve essential benefits while providing sources of supplemental support for the long term.

If you want to create your lifelong financial plan with advisors who have knowledge and experience working with disabled people and their families, let’s talk.

1. “Caregiver Statistics: A Data Portrait of Family Caregiving in 2023,” AARP, March 8, 2023.

2. “Persons with a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics Summary, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics,” Feb. 22, 2024.

3. “Long COVID Appears to Have Led to a Surge of the Disabled in the Workplace,” Liberty Street Economics, Oct. 20, 2022.

4. “Inclusive Postsecondary Education for Students with Intellectual Disabilities,” PACER, July 2024.

5. Special Olympics, July 2024.

6. “Disability in the Workplace: 2023 Insights Report,” National Organization on Disability.

7. “Disability Impacts All of Us,” CDC, May 2023.

Mercer Advisors Inc. is a parent company of Mercer Global Advisors Inc. and is not involved with investment services. Mercer Global Advisors Inc. (“Mercer Advisors”) is registered as an investment advisor with the SEC. The firm only transacts business in states where it is properly registered or is excluded or exempted from registration requirements.

All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the author as of the date of publication and are subject to change. Some of the research and ratings shown in this presentation come from third parties that are not affiliated with Mercer Advisors. The information is believed to be accurate but is not guaranteed or warranted by Mercer Advisors. Content, research, tools and stock or option symbols are for educational and illustrative purposes only and do not imply a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell a particular security or to engage in any particular investment strategy. For financial planning advice specific to your circumstances, talk to a qualified professional at Mercer Advisors.

Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards, Inc. (CFP Board) owns the CFP® certification mark, the CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER® certification mark, and the CFP® certification mark (with plaque design) logo in the United States, which it authorizes use of by individuals who successfully complete CFP Board’s initial and ongoing certification requirements.